The Definitive Guide to Package Managers

What they are, how they work, when to pick which one and the tradeoffs you must manage

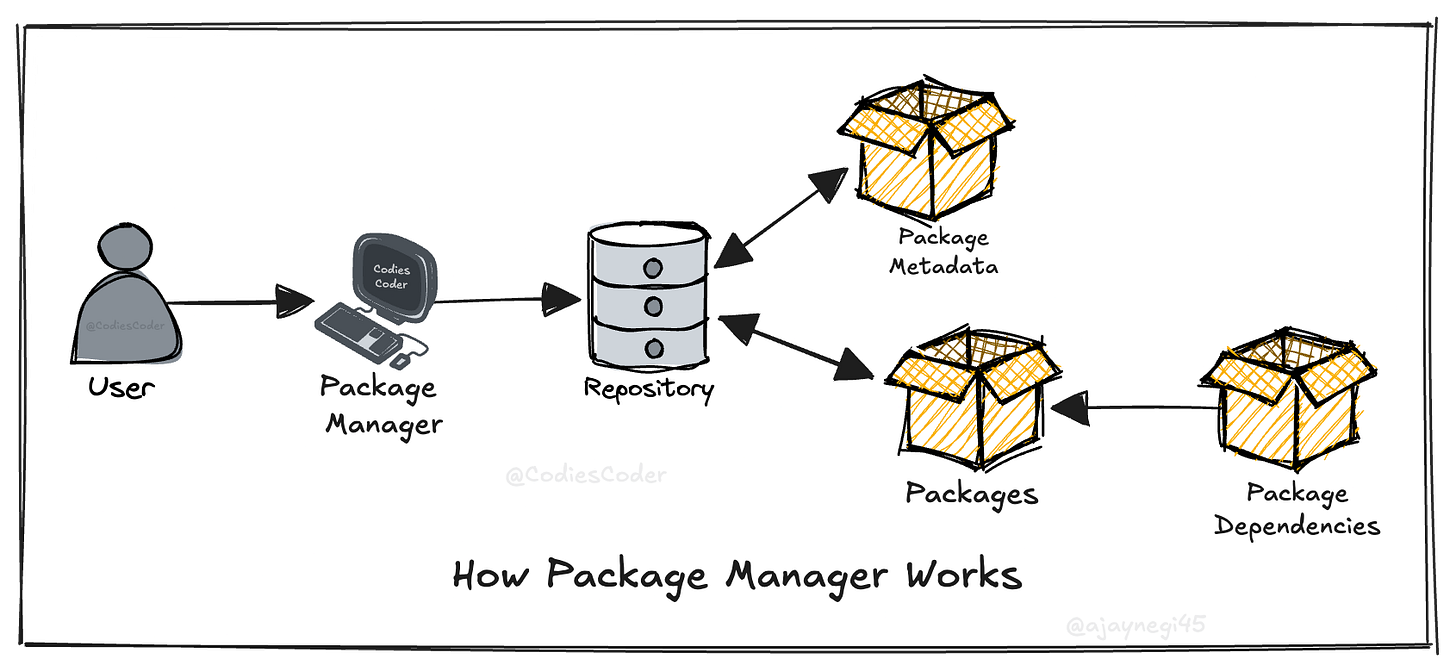

A package manager is software that automates finding, installing, upgrading, configuring and removing software packages in a consistent manner. Packages are archives that combine program files plus metadata (name, version, dependencies, checksums, scripts). Package managers maintain a local package database and interact with remote repositories to satisfy user requests and resolve dependencies.

Core concepts (building blocks)

Package — an archive with program files and metadata (version, dependencies, install scripts).

Repository (registry) — remote store of packages.

Package database (local state) — tracks installed packages, versions, files, and metadata.

Dependency metadata — declares what other packages (and versions) are required.

Resolver — algorithm that finds a set of package versions that satisfy constraints.

Installer/unpacker — extracts files, runs pre/post scripts, updates database.

Signing & checksums — integrity and authenticity mechanisms.

Architecture and flow (high level)

User requests install/update of package

A.Client queries configured repositories for available versions and metadata.

Resolver constructs dependency graph (transitive dependencies + version constraints).

Resolver computes an install plan (order, conflict resolution).

Client downloads package archives, verifies checksums and signatures.

Installer unpacks packages, runs lifecycle scripts, updates local database.

Post-install validation and cleanup.

Language-level Package Managers

Language-level Package Managers are tools that manage libraries and dependencies for a specific programming language. They handle installing, updating, removing, and resolving versions of packages required by a project.

They operate within the ecosystem of one language, ensuring compatibility with that language’s runtime, syntax and conventions. These managers typically use a configuration file to declare dependencies and a registry or repository to fetch them.

JavaScript / TypeScript

npm

What: Default package registry and CLI for Node and front-end packages.

When: Use for Node projects and most JS dependency management; default for publishing to the npm registry.

Advantages: Ubiquitous, integrated with Node, lockfile (

package-lock.json), huge ecosystem.Disadvantages: Historically large

node_modules, occasional supply-chain risks, some legacy behavior surprising (flat vs nested deps historically).

yarn (classic / berry)

What: Alternative npm client with performance and UX improvements (Berry = modern Yarn).

When: Use for faster installs, workspace monorepos, or when you need deterministic installs.

Advantages: Workspaces, offline cache, deterministic installs, performance.

Disadvantages: Divergent configs across versions; switching costs; some plugins required for parity with npm.

pnpm

What: Disk-efficient package manager using a global content-addressable store and hard links.

When: Use for large mono-repos or when you want strict node_modules invariants and minimal disk usage.

Advantages: Extremely fast; saves significant disk space; strict dependency resolution prevents “phantom dependencies” (accessing unlisted packages).

Disadvantages: Symlink-based

node_modulesstructure can break specific tools (some React Native, Electron, or serverless setups); requires strict declaration of all dependencies unlike flat-node_modules managers.

bun

What: JavaScript/TypeScript runtime with a built-in, high-performance package manager (

bun install) compatible withpackage.jsonand npm packages.When: Use when install speed and runtime performance matter, or for greenfield projects that benefit from an integrated toolchain (install, run, test, bundle).

Advantages: Very fast installs and startup, single binary toolchain, supports workspaces and standard npm dependency semantics.

Disadvantages: Younger ecosystem than npm/yarn/pnpm; some native modules and edge tooling may be incompatible; higher risk for large or legacy codebases.

Python

pip (+ wheel)

What: Python package installer; installs wheels/archives from PyPI.

When: Use for installing packages and simple apps; base tool in Python ecosystem.

Advantages: Standard, simple, broad PyPI coverage.

Disadvantages: Dependency resolution historically weaker (improved), no built-in env isolation.

venv / virtualenv (env managers)

What: Create isolated Python environments.

When: Always use for per-project isolation.

Advantages: Simple, standard.

Disadvantages: Manual activate step; dependency and reproducibility needs lockfiles.

pipenv

What: Combines

pip+ virtualenv + lockfile.When: Use when you want managed virtualenvs + automated lockfile workflow.

Advantages:

Pipfile+Pipfile.lockfor reproducible installs.Disadvantages: Performance and reliability complaints historically.

poetry

What: Dependency management and packaging tool with built-in lockfile and publish flow.

When: Use for modern project management, building, and publishing Python packages/app.

Advantages: Good UX, deterministic builds,

pyproject.tomlsupport.Disadvantages: Different command set; some ecosystem edge cases (C extensions) need care.

conda

What: Environment and package manager for Python (and binaries) focused on data science.

When: Use for data-science stacks, binary-heavy dependencies (numpy, MKL) and cross-language packages.

Advantages: Solves “binary compatibility” hell by managing non-Python libraries (libc, compilers) within the environment; truly isolated environments.

Disadvantages: Large installation footprint; slower dependency solver than pip/uv; separate channel ecosystem (conda-forge vs defaults) can cause conflicts.

Java / JVM languages (Java, Kotlin, Scala)

Maven

What: Build and dependency management using POM XML and Maven Central.

When: Enterprise Java builds, artifact publishing, transitive dependency management.

Advantages: Mature, strong repository ecosystem, plugin-rich.

Disadvantages: Verbose XML config; slower builds historically.

Gradle

What: Modern build tool (Groovy/Kotlin DSL) that replaces Maven for many projects.

When: Use for faster, scriptable builds, Android, Kotlin/Java projects.

Advantages: Incremental builds, flexible DSL, performance.

Disadvantages: Learning curve; complex build scripts can become hard to maintain.

SBT (Scala)

What: Scala build tool with its own dependency model.

When: Scala projects.

Advantages: Scala-centric features, interactive shell.

Disadvantages: Slow startup historically, idiosyncratic config.

Rust

cargo

What: Build system and package manager for Rust (crates.io).

When: Always use for Rust projects.

Advantages: Integrated build + test + publish; excellent dependency resolution; lockfile.

Disadvantages: Tied to Rust ecosystem only (not a drawback in practice).

Go

Go modules (go mod)

What: Native dependency management tracking modules and versions.

When: Use for all modern Go projects.

Advantages: Simple, versioned modules, reproducible builds with

go.sum.Disadvantages: Module proxy complexity and historic GOPATH transition confusion (now stabilized).

Ruby

RubyGems

What: Package format and installer for Ruby gems.

When: Use for installing libraries and CLI tools in Ruby.

Advantages: Standard, integrated with Ruby ecosystem.

Disadvantages: Gem native extension builds can be painful across platforms.

Bundler

What: Dependency manager that locks gem versions for apps.

When: Use for app dependency management and reproducible deployments.

Advantages:

Gemfile.lockdeterminism; widely adopted.Disadvantages: Management of native gems remains an operational concern.

PHP

Composer

What: Dependency manager for PHP (Packagist registry).

When: Use for PHP projects and frameworks.

Advantages: Semantic versioning, autoloading support, lockfile.

Disadvantages: Dependency resolution can pull large graphs; autoload metadata overhead.

.NET (C#, F#, VB)

NuGet

What: Package manager and registry for .NET assemblies.

When: Use for .NET library and app dependencies.

Advantages: Tight integration with MS build tooling and Visual Studio.

Disadvantages: Multi-targeting and runtime-compat issues require attention.

C and C++

conan

What: C/C++ package manager for binaries and sources.

When: Use to manage C/C++ libraries across platforms and compilers.

Advantages: Binary recipe support, configurable build profiles.

Disadvantages: Extra learning; build matrix complexity.

vcpkg

What: Microsoft-backed C++ package manager focused on Windows and cross-platform.

When: Use for quick consumption of popular C++ libs in MS ecosystems.

Advantages: Good Windows integration, simple consumption.

Disadvantages: Less flexible for custom build pipelines.

Swift / Objective-C (iOS/macOS)

Swift Package Manager (SPM)

What: Official package manager for Swift.

When: Use for Swift libraries and apps, server-side Swift.

Advantages: Native integration with Swift toolchain; simple manifest.

Disadvantages: Historically less feature-rich than CocoaPods for iOS resources (closing gap).

CocoaPods

What: Dependency manager for Obj-C/Swift with a Podspec system.

When: Use for iOS projects that rely on wide third-party pods.

Advantages: Mature, handles resources and frameworks.

Disadvantages: Alters project files, slower installs.

Carthage

What: Decentralized iOS dependency manager producing binary frameworks.

When: Use when you want minimal project modification.

Advantages: Non-invasive.

Disadvantages: Less automated than CocoaPods; manual integration steps.

Haskell

Cabal / Stack

What: Cabal is package format; Stack is a build tool that pins resolver snapshots.

When: Use Stack for reproducible builds; Cabal for library packaging.

Advantages: Strong type-level package bounds, curated Stackage snapshots.

Disadvantages: Learning curve; platform-specific build complexity.

Elixir / Erlang

Hex (Hex.pm)

What: Package manager for Erlang/Elixir packages.

When: Use for Elixir/Erlang dependencies.

Advantages: Lightweight, mix integration (Elixir build tool).

Disadvantages: Smaller ecosystem than mainstream languages.

rebar3 (Erlang)

What: Erlang build tool and dependency manager.

When: Erlang projects.

Advantages: Erlang-focused features.

Disadvantages: Less ergonomic than some newer tools.

R

CRAN / tools like packrat, renv

What: CRAN is the central R repository; renv/packrat manage project environments.

When: Use renv/packrat for reproducible R project environments.

Advantages: Statistical-package ecosystem; renv gives per-project reproducibility.

Disadvantages: Binary dependencies and system libs complicate reuse.

Perl

CPAN / cpanminus (cpanm)

What: CPAN is the central archive; cpanm is a lightweight client.

When: Use cpanm for fast installs; CPAN for published modules.

Advantages: Huge historical collection.

Disadvantages: Native extensions and build tooling variability.

Lua

LuaRocks

What: Package manager for Lua modules.

When: Use for Lua dependencies.

Advantages: Simple, ecosystem-focused.

Disadvantages: Platform-native builds can be brittle.

Dart

pub

What: Package manager and hosting for Dart/Flutter packages.

When: Use for Dart and Flutter projects.

Advantages: Integrated, pub.dev ecosystem, lockfile support.

Disadvantages: None major; tied to Dart ecosystem.

OS-level Package Managers

OS-level Package Managers are tools that manage system-wide software and libraries for an operating system. They install, update, remove, and maintain applications and system dependencies used by both users and programs.

They operate at the operating system level, handling compiled binaries, system services, and shared libraries. These managers ensure compatibility with the OS, manage permissions, and maintain system stability.

Linux (Debian-based)

APT (Advanced Package Tool)

What: Package manager for Debian, Ubuntu, and derivatives using

.debpackages.When: Use for system libraries, services, CLI tools on Debian/Ubuntu systems.

Advantages: Stable, large repositories, strong dependency handling, signed repos.

Disadvantages: Older versions in stable releases; mixing PPAs can break systems.

dpkg

What: Low-level

.debpackage tool used by APT.When: Use for manual install/remove of local

.debfiles.Advantages: Direct control, minimal abstraction.

Disadvantages: No dependency resolution by itself.

Linux (Red Hat–based)

YUM (legacy) / DNF (modern)

What: Package manager for RHEL, CentOS, Fedora using

.rpmpackages.When: Use for system management on Red Hat-family systems.

Advantages: Strong dependency resolution, modular repos, enterprise support.

Disadvantages: Slower metadata operations; repo fragmentation across vendors.

RPM

What: Low-level package format and tool.

When: Inspect or install RPMs directly.

Advantages: Fine-grained control.

Disadvantages: No dependency resolution alone.

Linux (Arch-based)

pacman

What: Package manager for Arch Linux and derivatives.

When: Rolling-release systems requiring latest software.

Advantages: Simple, fast, consistent syntax.

Disadvantages: Rolling releases can introduce breaking changes.

Linux (Universal / Cross-distro)

Snap

What: Canonical’s sandboxed package system.

When: Use for isolated desktop/server apps across distros.

Advantages: Self-contained, auto-updates, sandboxing.

Disadvantages: Larger disk usage; slower startup; centralized control.

Flatpak

What: Desktop-focused sandboxed package system.

When: Use for GUI apps on Linux.

Advantages: Strong isolation, distro-agnostic.

Disadvantages: Not ideal for system services; runtime duplication.

AppImage

What: Single-file portable Linux application format.

When: Use for standalone apps without installation.

Advantages: Zero install, portable.

Disadvantages: No auto-updates or dependency management.

Linux (Functional / Reproducible)

Nix (NixOS / nix-env / nix-shell)

What: Purely functional package manager with immutable store.

When: Use for reproducible builds, dev environments, infra-as-code.

Advantages: Reproducibility, rollback, no dependency conflicts.

Disadvantages: Steep learning curve; nonstandard filesystem layout.

Guix

What: GNU functional package manager similar to Nix.

When: Same use cases as Nix, GNU-centric systems.

Advantages: Declarative, reproducible.

Disadvantages: Smaller ecosystem than Nix.

macOS

Homebrew

What: Widely used macOS package manager for Unix tools and apps.

When: Install developer tools, CLIs, runtimes on macOS.

Advantages: Massive ecosystem (”bottles”); easy installation of latest versions; handles distinct formulas and casks (GUI apps).

Disadvantages: Rolling-release model makes version pinning and rollback difficult (non-deterministic); modifies

/usr/localor/opt/homebrewwith user permissions, effectively bypassing some system isolation protections.

MacPorts

What: macOS package manager with isolated prefix.

When: Need strict dependency isolation.

Advantages: Predictable builds, isolation.

Disadvantages: Slower; smaller community than Homebrew.

Windows

Chocolatey

What: Windows package manager for apps and tools.

When: Automate Windows dev machine setup.

Advantages: Scriptable installs, wide catalog.

Disadvantages: Packages often wrap installers; quality varies.

Winget

What: Official Windows Package Manager by Microsoft.

When: Standardized Windows app installation.

Advantages: Native, improving rapidly, trusted source.

Disadvantages: Smaller ecosystem than Chocolatey (for now).

Scoop

What: Lightweight Windows CLI package manager.

When: Install developer tools without admin rights.

Advantages: Simple, user-local installs.

Disadvantages: Smaller catalog.

BSD Systems

pkg (FreeBSD)

What: Binary package manager for FreeBSD.

When: Manage system packages on FreeBSD servers/desktops.

Advantages: Clean dependency handling, stable repos.

Disadvantages: Smaller ecosystem vs Linux.

Ports Collection

What: Source-based package system.

When: Custom compile-time options needed.

Advantages: Maximum control.

Disadvantages: Slow builds; manual effort.

Solaris / Illumos

IPS (Image Packaging System)

What: Package system for Solaris-derived OSes.

When: Enterprise Solaris environments.

Advantages: ZFS integration, atomic updates.

Disadvantages: Niche ecosystem.

When to use OS-level vs Language-level managers

Use OS-level package managers when:

Installing system-wide services, kernels, or drivers.

Managing base server images and security patches.

Exception: Functional package managers like Nix and Guix are OS-level tools that can handle per-project isolation effectively, blurring this line.

Do NOT use OS-level managers when:

Managing application dependencies inside a project

You need per-project version isolation

Reproducibility across machines matters

Use language-level managers for apps, OS-level managers for the system.

Dependency resolution — the hard part

Dependency resolution is where most complexity and subtle bugs happen.

Constraint types: exact, range (semver), open (latest), exclusion.

Solver strategies:

Greedy (fast, may fail on complex constraints)

Backtracking SAT-like solvers (complete but slower)

Deterministic pinning (freeze a full lockfile)

Conflicts: two packages require incompatible versions of the same dependency — resolution strategies include upgrade, downgrade, multiple side-by-side installations, or refusing install.

Transitive explosion: small change can pull many packages; lockfiles and reproducible builds mitigate this.

Practical pattern: for applications, prefer lockfiles (exact pins) and reproducible installs. For system packages, use conservative upgrades and well-curated repositories.

Security: integrity, provenance, and supply-chain risks

Key controls:

Checksums: verify downloaded archives against published hashes.

Signing: GPG/PGP signatures for packages and repository metadata; prevents tampering and impersonation.

TLS + repo auth: secure transport and authenticated registries for private packages.

Least-privilege install: avoid running install scripts as root when unnecessary.

Reproducible builds: allow independent verification that binaries come from source.

Monitoring & scanning: vulnerability scanners (Snyk, OSS Index), artifact scanning in CI.

Reality: public registries have been exploited (typosquatting, malicious packages). Mitigations: scoped registries, allowlist, signing, internal mirrors or proxies.

Operational patterns and CI/CD integration

Artifact repositories: publish built artifacts (binaries/wheels/images) to a controlled registry from CI. Avoid building in production environments.

Promotion model: publish to staging repo → run integration tests → promote to production repo (immutable artifact promotion).

Immutable artifacts + rollbacks: keep old artifacts for rollback; use exact pins in deployment.

Cache layers / proxies: use caching proxies (e.g., Artifactory, Verdaccio) to reduce external outages and improve reproducibility.

Automated dependency updates: Dependabot/renovate for PRs; but guard with tests and gated promotion.

Common failure modes and how to avoid them

Dependency hell: conflicting transitive deps. Avoid by strict pinning and prefer single-source dependencies when possible.

Left-pad problem / small malicious packages: one small package can break large ecosystems. Favor vetted, well-maintained dependencies.

Broken install scripts: lifecycle scripts run with privileges can cause system instability. Avoid unnecessary scripts; validate before merging.

Registry outages: use mirrors and caches; vendor critical dependencies.

Ambiguous ownership: packages overwritten in repos by mistake. Enforce signing, access controls, and CI gates.

Design considerations for writing and maintaining packages

For package authors:

Provide complete metadata (name, description, license, homepage, author, version, dependencies).

Keep install scripts idempotent and safe to re-run.

Avoid assuming global mutable state; allow relocatable installation where feasible.

Include checksums and signatures for binary artifacts.

Publish artifacts built in CI (not developer machines); store build logs and provenance.

Maintain a clear deprecation and migration path for breaking changes.

For repository maintainers:

Enforce review policies, sign packages, and scan for known vulnerabilities.

Support artifact immutability and retention policies.

Expose clear version compatibility and support windows for major breaking changes.

Emerging trends and alternatives

Functional/package managers (Nix, Guix): treat packages as immutable derivations, enabling per-user installs and reproducible environments.

Artifact registries & SBOMs: Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) for supply-chain visibility.

Container-centric deployments: shift packaging from language managers to OCI images, reducing cross-language dependency issues but shifting complexity to image build pipelines.

Package signing adoption: more registries require signatures and provenance metadata.

Do you know someone who loves engineering or has a curiosity for tech? 🤔

Why not share the joy of simplifying complex ideas with them? Forward this newsletter and spread the knowledge—learning is always better when it’s shared! 🚀